The music is still playing in my head.

Its the normal mark of an auditory learner, I think, to have permanently lodged in our short-term memory the most recent song that was playing before we parked the car, or got off the bus. You know what I mean…you’ll be humming it to yourself all day until you’re finally leaving the office, or until you have the chance to listen to something else while you plow through your paperwork. There’s nothing to be ashamed of in that…it just means that music’s staying power and beauty isn’t lost on you.

The music in question has been playing in my head since last night. Its not the last thing I listened to on the flight home from the family’s Thanksgiving celebration, its not the jazz I played while reading last night. It the theme song to the DVD I finished watching last night in order to return it to Netflix this morning, and it was (cough)…it was an (looking down, shuffling feet)…it was sort of an…a 1980’s superhero cartoon theme song.

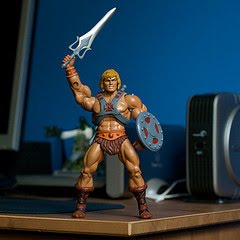

Okay, I said it. I’m out of the closet now. Last night’s bedtime entertainment for me was a DVD of the top five episodes of the first season of He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. I remarked to Karen that something about the sounds of the opening credits and theme song/voiceover took me back to my elementary school days, back to a simpler and innocent time. Maybe I was just justifying it to myself…maybe. More likely, I was justifying my viewing choice to her…but that’s okay, she loves me and accepts me. What was profoundly of interest to me last night, though, was watching an animated fantasy series from my elementary school years through the lens of education and sensibilities that come with me in life currently…sort of a metaphysical inspection, if you will. All good science fiction (and all good stories of any genre) have a meta-message of some variety, and animated series are no different. I’m not aware of scholarly discussion about He-Man, although that’s not to say that it isn’t out there, but I remember the series being of intense interest to me in my young impressionable years. I remember talking on the playground to another guy one morning, the morning of the day that He-Man’s premiere was due to air. He asked me if I was going to watch it. I responded with an enthusiastic “yes!” A girl was there. She shook her head and turned to friends to discuss how incredibly immature this was.

He-Man was controversial in the animation world because of its previously un-matched violence in American animation. I can see overtly masculine images and appeal in the show now…it was, and is, all about connecting to a young male audience. He-Man was, simply, the hero we all hoped to be, the other identity that I knew lay somewhere underneath my nerd’s exterior, that would surface and run to the rescue should the need ever arise in one of my peers…preferably an attractive one of the opposite gender.

I remember having a dream about a beautiful girl that needed help. I ran to her aid, leading the others in my elementary school class behind me. I was the heroic leader, charging forward to save her honor. Very He-Man-like. I always liked that dream.

You see, every boy…every man…everyone…dreams of being a hero in some regard. We long to leave a legacy, to depart this realm with the knowledge that we’ve accomplished something, that our lives stood for something and will leave something positive in their wake. Deep down, I always wanted to save the damsel in distress. I always wanted to be a hero to those in crisis. I always wanted to save the day.

Not long after I was out of college, I was driving somewhere after work one afternoon. I remember that my mother was in the car with me. I was navigating out of a parking lot, when an elderly woman mis-judged a turn and hopped a concrete barrier that stood in the way of a large, ravine-style ditch. Her car slammed down on the concrete barrier rather violently as her tire slipped off the edge. Liquid immediately began flowing from underneath. I got out of our vehicle to smell that it was fuel. She had ruptured her fuel tank, and was attempting to rock the car back over the barrier, creating the risk of potentially making a spark. While someone else called the police, I convinced the woman to place her vehicle in park, and assisted her away from the car until emergency crews arrived. I felt like a superhero. I felt like I had saved the day.

Maybe I’m making too much of a relatively minor incident, but I like to recall that moment sometimes in the belief that I helped someone. Perhaps I entered the field I’m in with a sort of superhero complex, wanting to save the world, one client at a time. Perhaps that is the alter-ego of the writer…perhaps I write as Clark Kent, while convincing myself that I can leap tall buildings in a single bound as I go to work each morning.

Perhaps that’s pretty sad, but I take comfort in the fact that I can at least know that I’m trying to make a difference to others, even if I don’t succeed. And I’m not alone, because, if I were, fantasies like the world of He-Man and countless other superhero adventures wouldn’t resonate with humanity like they do, existing cross-culturally in genres of literature around the world.

If the only person I’ve ever helped was the elderly woman that day, then I feel like I counted for something. Even if there was no theme music playing or light flashing of magical swordplay.

That, I think, is why He-Man takes me back to a time of innocence, when I dreamed of what I wanted to accomplish, of the difference I wanted to make. And, that is likely why these stories appeal so heavily to me today, because I hope that I’m not through making a difference quite yet.

That’s what I’m thinking, anyway. I may even have more to say later this week, because Inhumanoids is next in the cue.

Photo Attribution: